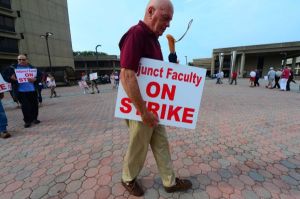

With ever more attention focused on the plight of adjuncts – their burdensome and under-compensated teaching, their outsized role in undergraduate instruction, their cheapened existence in a neoliberal university – I wanted to think out loud about how to treat contingent and temporary teachers.

Obviously, I’m trying to think of a productive middle ground between the hardline stance of prominent critics, who simply say “don’t hire adjuncts,” and the sometimes willful ignorance of those already safely and luckily tucked into the tenure stream at this moment of great transformation. And more to the point, since temporary teaching appointments are typically made by chairs (in my limited experience at three different institutions), this is something I can actually do.

For those who haven’t been following the news: adjunct faculty, teaching without benefits, with generally pathetic wages, and often marginalized in their departments and institutions, now comprise roughly 70% of the teaching capacity of the American university. Some institutions are worse and some are better, and some specializations are hard hit and others aren’t, but this “adjunctification” is getting worse, as universities look to have a nimbler work force, easily trimmed in moments of crisis or expanded in moments of need, with less exposure to ever-escalating health care costs. When you hear people talking about universities and colleges as the new “Wal-Mart,” this is what they’re referring to; and when you hear people discuss the unionization of adjuncts, this disturbing process is why.

It can be daunting to imagine making a real change. And some issues – extending benefits, for instance – are going to be very, very difficult. But, for any willing chair, there are areas directly under your control that can addressed in fairly short order, I think.

1. As the controller of space in my department, I can guarantee temporary teaching faculty space – an office of their own, either borrowed from someone else on leave or simply assigned out of available rooms. And I can limit the number of these appointments so that they match available space. No office hours at Au Bon Pan, please. An office is not only for meetings with students, after all.

2. As chief budget officer, I can provide support for research and travel to match that given to tenure stream faculty. I have to pay for it differently, because some pots of money come from outside the department. But it can be done, especially if we limit the number of appointments.

3. I can ensure that their teaching is valued by investing in it. I can ask them to attend workshops on teaching at our local pedagogy center, ask tenured faculty to watch them teach and to place constructive evaluations in their files. If I have a department teaching award under my control, I can include them in the pool of meritorious candidates. I can be prepared, then, to write a letter of recommendation for them if they need it, with a fulsome reference to their work in the classroom.

4. I can take their research seriously, which means giving them an opportunity to share it with our faculty and graduate students and, again, giving them a fair pool of resources. But it also means that I should care about where they are going as writers, and get them good readers to help them along.

5. I can include them in our faculty meetings as active discussants. They couldn’t participate in personnel discussions, because their voices and votes wouldn’t be legible to the outside world. But for the rest, they could help to shape department policy and practice, but only if they were willing and able to do so.

6. I can ensure that they are represented on our website as members of our core faculty. This means, simply, that they should be mixed up in the alphabetical list of faculty, given a full description of their research and teaching, a picture, a useful title, etc.

7. I can make sure they are paid the best wage possible. That I take evaluations of their teaching into account when I make decisions about reappointment. That I meet with them every semester to discuss their work for the department. And that, when someone asks me, “hey, do you have anyone who does X,Y, or Z,” that I consider these folks as people who represent the department.

8. I can appoint fewer of them, because I’d like to imagine what they can contribute to the department beyond merely generating student credit hours. I can provide them with a diversity of teaching options.

9. I can be totally candid with them about the chances of their getting a tenure stream job in the department. Those chances aren’t quite zero, but they also aren’t 50/50. And the longer they work off the tenure stream, the less likely they are to match what we’re going to be looking for whenever a search opens up.

10. I can remind myself over and over again that these are not full-time, tenure stream faculty. And as a consequence, they can’t do more and they have to do less. In much the same way that we are supposed to attend to the teaching and service of jointly-appointed folks, I need to make sure they perform service that matches their compensation.

11. I can vociferously defend their right to academic freedom.

12. I can ask myself – repeatedly – why my department needs any adjuncts at all. If the answer is that core faculty aren’t willing to teach some classes, or that adjuncts alone can teach the classes that generate credit hours, then something has gone wrong. That something doesn’t have anything to do with adjuncts at all. It has to do with the exploitation of cheap labor for the benefit of a few. And it should be addressed.

Not all of these are possible everywhere, but most of them are.

27 responses to “Adjunct Apocalypse”

[…] What chairs can do for adjuncts, today. Informed and realistic, striking precisely because the suggestions are so […]

LikeLike

Wow! I wish there were more chairs like you out there!

LikeLike

Where are you? We don’t have those kinds of rights and job conditions as tenured faculty! And: the adjuncts, who don’t even have Ph.D.s, have more job security and rights than we do! And: when I said they should have access to travel funds (about 10% of the cost of a conference can be reimbursed), they said I was oppressing them by thinking they should go to conferences! (I wasn’t even saying they should have to present, I was saying they should have support to go!)

LikeLike

Ah, but I see, Brown, a place with funding, now I understand. If we had Ph.D. researchers as adjuncts, which we do not since it is unethical, we would treat them like regular faculty, just as we do the M.A. contingent people (who are not part timers, but are FTEs with PhD-size offices and everything).

I have one question about all of this: do tenure-track and tenured faculty elsewhere actually have the right to refuse to teach certain classes? I have worked at a fancy SLAC, a pretty good R1, as a VAP at 2 better R1s, and at the current R2-ish place, and I have never dreamed of refusing a course I was assigned, and I have never met anyone else who did.

Is it possible to do that at some places, i.e., say, oh, I don’t want to teach that, hire an adjunct for it? The *only* times I have questioned a teaching assignment were (a) when a colleague with kids and a certain schedule wanted to trade courses with me, because of the time, and I said sure, and we went to the chair on it, and (b) when I got assigned a graduate seminar way out of field, that I knew there were no students for. I knew the schedule had been made by the adjunct in charge of that and that this was a non-malicious error, so I went to the chair and asked to teach a different topic. (I was at the time a little worried what he would think of my saying this preparation would be such a reach for me.) Anyway: do your faculty actually flat-out refuse to teach certain courses? Do you not have the power to tell them they have to? Am I in an alternate universe?

LikeLike

On the east coast, Z. I agree that this would harder at some places.

LikeLike

OK so therapy. Do you think it would be reasonable for me to ask dept chair to release me from the basic language sequence (I am in a foreign language)? I have been tenured for 12 years. Basic language sequence is very painful because of the autocratic and rather incompetent leadership of the adjuncts in charge, and there is a lot of discrimination against people trained to teach in a more modern way. I suffer a lot in it and it is very bad for me professionally. But I teach in it, I am told, because I must “make it up” to the adjuncts who “have not had the chance to do a Ph.D.” by letting them teach the intermediate courses. I want to flip this around: since they are directing the language program, let them staff it. Is this in any way fair? I have all kinds of courses I could give that would be good for the university, and I speak native English so I am able to teach in that language as well. Am I unreasonable to think this is a good idea, or by even asking am I discriminating against the M.A. adjuncts and claiming to be “better than they are” (the big issue here)? (I wouldn’t say “better,” I do say different, different education, different interests, different goals, but here there is this whole ethos about people who have done the Ph.D. thinking they are “too good.”)

LikeLike

P.S. I am still just curious. So at your place, people on the tenure track can just say, oh, I do not want to teach that, please hire me an adjunct for it?

LikeLike

It doesn’t quite work like this, of course. Brown has an open curriculum, with far fewer required courses. And I’m in a department without a typical service course. And I’m not in a language department. That changes things. Where we hire non tenure track faculty, we do so to cover a field or an area that is otherwise uncovered. Maybe because someone is on leave. Or maybe because someone has left. And these adjuncts teach small topical electives, usually, in an area of their choosing.

But, over the long haul (and not here), I have certainly known tenured and tenure-stream faculty to turn down a teaching assignment or decline to teach a particular class. In those cases, hiring an adjunct is one possible solution. Another – one I’ve used myself (not here) – is to teach the class myself, to free up room for someone to do something else. People say “no” for lots of reasons, including to develop new classes in new areas. Hope this makes sense.

LikeLike

Another question and I will be quiet. (You not only have more budget than I am used to, you also have more power as chair than do chairs at most places I have worked.)

On this: “But for the rest, they could help to shape department policy and practice, but only if they were willing and able to do so.”

I advise *against* this. It is what we do and it is a serious problem. It means people with an M.A., who have been hired off the street and get rehired and rehired because we are desperate, have veto power on everything, yet are not required to carry a full service load. So the tenure-track and tenured do the work, and the contingent people with little training and no continuing professional development knock it down, trying to get things back into the 1950s or whatever decade they are comfortable with. It has to be yes or no: people either have service responsibilities or they don’t. If they do, they have to come through on them. Otherwise you get mayhem. I speak from long experience.

LikeLike

P.S. what I mean by this is that at my place, respect for the contingent has gone too far. Because they are over half the faculty, and they don’t go through the kind of rigorous review research faculty do, and so on, they have really taken over in terms of policy making and so on. It is them and the administrative staff, who have no real academic experience, either. So I am very suspicious of the adjuncts rights movement for this reason: they support the administration and have to s*** up to it since they are contingent, and the administration supports them since they are cheap, which means people with PhD and research agenda are marginalized in the corporate university. I am all for being nice to adjuncts and I am, but I think the be-nice-to-adjuncts movement when it focuses only on that, is blind to the larger contours of the adjunctification and corporatization problem and is also complicit in the demise of the non-corporate university.

LikeLike

“I can be totally candid with them about the chances of their getting a tenure stream job in the department. Those chances aren’t quite zero, but they also aren’t 50/50. And the longer they work off the tenure stream, the less likely they are to match what we’re going to be looking for whenever a search opens up.” Why is this the case? Is there a rational reason for this that I’m not seeing?

LikeLike

I wouldn’t call it rational – but, over time, the system doles out material benefits to those on the tenure track and denies the same to adjuncts. So, as one year becomes two and so forth, adjunct faculty come to look, on paper, quite different. They’ve been starved of resource support for conference travel, research, etc. And that has an impact on their profile in any job search.

LikeLike

What about in comparison to brand-new PhDs, though? I tend to think that if they haven’t been hired out of graduate school then there must be some Issue with them, so I want a new PhD, but I think this may be unfair of me. Advantages of people who finished and then were contingent is that they have FT experience post dissertation. This can be a good thing. What do you think, or are you comparing these people to an applicant pool of advanced asst profs who have had research support?

LikeLike

And, I have a different question. “And the longer they work off the tenure stream, the less likely they are to match what we’re going to be looking for whenever a search opens up.”

***If they have PhD and are publishing and so on, functioning like tenure-track people, how is this true? I have my answer for it but I am just curious as to how someone else would put it. In my field (a) the only reason they would not be TT is really weak dissertation or something like that (we do not have a job crisis in my field); (b) from there, they may be publishing in peer reviewed places, but not in first tier journals. But what if they ARE publishing in top places, and so on: is it a stigma that they have adjuncted?

(I have to say, I am prejudiced myself, tend to find it odd when people have not landed real jobs, wonder what is up with that, i.e. whether they are a sexual harrasser and we have not heard yet, things like this. I believe I have made errors in the past, being too suspicious. Yet sometimes I have also erred in the other direction. I don’t know what to think.)

LikeLike

“But, over the long haul (and not here), I have certainly known tenured and tenure-stream faculty to turn down a teaching assignment or decline to teach a particular class. In those cases, hiring an adjunct is one possible solution.”

I am amazed. Do you mean, people saying they prefer a different course, or people flat out refusing? I mean: saying one would rather teach x than y is one thing. I have gotten out of teaching assignments that were way out of field, or that I am not qualified for according to accreditation boards. But to say a flat no to a course, and having the department actually spend money to accommodate one in that, I have never seen even at fancy R1s. Amazing.

LikeLike

“Brown has an open curriculum, with far fewer required courses. And I’m in a department without a typical service course.”

That would be wonderful. And the open curriculum is *such* a good idea — I suppose that is how one would describe the requirements at my undergraduate place, and it was *so* much better than the arcane and complex requirements that have at existed at the places I have taught.

LikeLike

“Where we hire non tenure track faculty, we do so to cover a field or an area that is otherwise uncovered. Maybe because someone is on leave. Or maybe because someone has left. And these adjuncts teach small topical electives, usually, in an area of their choosing.”

OK, I see. So you are covering a gap, that may have come up suddenly, and vetting candidates less closely, hiring people you would not consider for tenure track jobs … partly because you can’t get the quality you want when you only have a fill-in job, and perhaps sometimes because you haven’t decided whether or not you want to hire someone permanent in their area?

So then, this is different from staffing an entire department with contingent people as a way to avoid hiring on the tenure track, right?

I am also trying to digest this idea of simply turning down a course. It seems so adult. It seems to be something faculty might be able to do at a place where they were thought of differently than they have been at the places I have worked. To do that you would probably have to have a grant of book project the university respects and supports, right? And not be “in a narrow field the university does not support,” as external reviewers said as a reason to turn down my last institutional grant application, right? So that, when you said look, there are better things I could do for the university than teach that course, those things you said you could do and have to do would be things they respected and desired, right? (Sorry for long windedness, I am just trying to imagine what it would be like to be treated that way as a professor / member of research faculty … and I really am curious, what does your view of the faculty member have to be for you to say, when they turn down a teaching assignment, all right, I’ll get an adjunct? Do you assign them something else, or do you just have them teach one course less in these cases? Does the university have to care about student credit hour production?)

LikeLike

People say ‘no’ all the time, but the institutional response differs dramatically depending on a lot of factors. I’ve never been at a place where courses were just assigned without conversation. And the conversation – at three very different places – has always started with a solicitation of teaching preferences from the faculty. Some volunteer to teach that big lecture class to generate credit hours, and some say, flat out, “I won’t ever do that.” The pressure to hire an adjunct is surely much greater at RCM institutions, where those credit hours determine the fates of departments. But even in those places, people still say “no.”

LikeLike

Oh, conversation happens at all of the places I have taught, but mostly you know ahead of time what is going to have to fall to you because of needs.

Perhaps I am reading you too literally, thinking of a scenario where people said gosh, I don’t feel like teaching that, let’s hire an adjunct for it — although given the funding, it would be amazing to be in a position to say such a thing.

At a whole other level, I am trying to get up the courage to say gosh, I have expertise in X and you are assigning it to people who do not, while I am teaching under them courses that they designed, this makes no sense … and knowing that if I say that, I will be told I am acting “entitled” and I have no right … and realizing how authoritarian the systems I am used to are, and how scarred I am by it.

LikeLike

[…] commented madly on this post today and it was because I was trying to imagine what it would be like to be a professor who was […]

LikeLike

I find this manifesto quite admirable, and I hope you can push for change. One thing, however.

While you do indeed gesture to your “limited experience,” I do want to make the point (and I’d ask you to do the same more explicitly) that the decisions you describe are not, in most institutions, up to the chair of the department. They are almost entirely up to some kind of administrator: Provost, Dean of Faculty, Association Dean of Faculty, etc. etc. etc.

The reason I make this point is to deflect, partially, the idea that most tenured and tenure-stream faculty have much control over the adjunctification of their own department. The large majority of us have little control, and the corporatization of Higher Ed has gone forward mostly at the behest of its management class, not the teaching faculty. So, while you seem to have real agency here, I hope your readership understands that this is NOT the case at most places!

LikeLike

Fair enough.

LikeLike

MPG:

Do you find that the use of adjuncts has the effect of swinging control over department curricula away from the regular faculty and towards administration?

In my own department, something like this has occurred: administration told the department it needed to make software training and internships a part of the undergraduate major. The regular faculty wanted nothing to do with this. But rather than fight it, they simply had adjuncts teach the major’s new software and internship classes. The long-term effect has been that all the department’s undergrads are interested in software and internships rather than in the research the regular faculty actually do. When regular faculty finally meet the undergrads in senior seminar, they’re startled to find they have nothing in common intellectually with their own majors.

Is this just my experience in my own department?

LikeLike

I don’t have exactly that experience but more generally, I would say yes, contingent faculty (FTE instructors without terminal degree) and administration work together, with the gen ed students, against the majors and the research faculty. This is why I am *not* for adjunct rights the way everyone else is. We have these people without full professional expertise running things as a result of making them 60% of the faculty and giving them big offices and a vote. It is detrimental, especially since they don’t come up for tenure or other serious reviews like that, but stay for decades. This is what the administration wants, for corporatization ! ! ! This is why I think the be nice to adjuncts movement is complicit with corporatization, and we must say tenure track or bust!

LikeLike

MPG,

I wonder if you’re also taking steps to protect your own students from being forced into adjuncting just to pay the bills. The Brown graduate school’s newish funding regime makes it more difficult to pursue the strategy of stretching your PhD out another year if you don’t make out on the tenure-track job market while ABD. And the policy of providing health insurance but not stipends to many advanced graduate students effectively subsidizes adjunct labor at other nearby universities.

LikeLike

Yes, as best as I can. I try not to blog about my own shop, so I don’t want to say more. But the solution here – the protection you reference – is necessarily comprehensive, affecting graduate education in any field from Day 1 to year 5, 6, or 7 and beyond. Email me offline if you want to talk.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on As the Adjunctiverse Turns and commented:

yet another on how to treat contingent faculty and temps … short of throwing $$ of course … found on Vitae’s Weekly Read Round-up

LikeLike